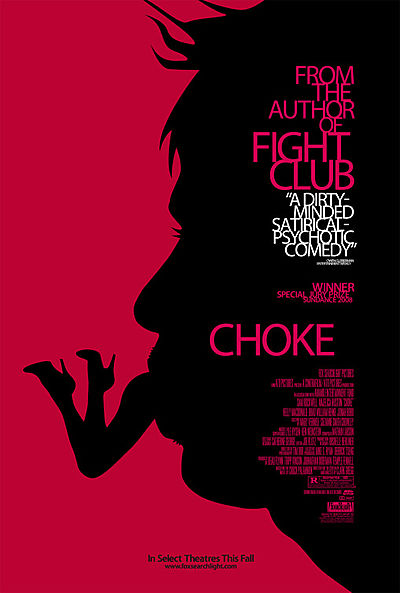

Childhood pangs of loneliness and parental discord are important features of the black comedy “Choke.” An adaptation of Chuck Palahniuk’s 2001 novel, the picture is a difficult amalgamation of tones and characters, lacking a needed core, but nevertheless remains an engrossing observation of diseased people engaged in self-loathing behaviors.

An employee at a Colonial recreation tourist destination, Victor (Sam Rockwell) spends his days barely tolerating his job, and his nights toying with sex addiction and petty scams. His mother (Anjelica Houston) is in a nursing home with dementia, and Victor struggles with his painful past, where he bounced around foster homes while his damaged mother berated his behavior and filled his head with deceit. When a kindly doctor (Kelly Macdonald) enters his life, Victor feels the uncomfortable onslaught of love filling his soul, only he hasn’t a clue how to process it, leaving him at a loss how to deal with the women in his life, and the growing 12-step peace changing his friend Denny (Brad William Henke).

“Choke” is a tricky film to deconstruct; it’s a charmingly low-budget character piece that’s episodic in nature, leaving the viewer to examine the overall experience, not necessarily the working parts. Writer/director Clark Gregg shifts the events around with the concentration of a chess match, trusting brief glimpses of Victor’s life throughout the years will add up to a fascinating whole. It’s a commendable attempt to observe a fractured life in a splintered manner, but I must admit that “Choke,” as carefully studied as it is, loses something in the translation from book to film.

Gregg is careful to retain the puckered Palahniuk tongue, building the personalities through immensely entertaining bursts of dialogue, pacing the interaction here with speed and caustic wit. Victor is like a contaminated Rat Pack member, stumbling through his life as an open wound, but armed with allure even he doesn’t fully understand. It’s a startling lead performance by Rockwell, who really grabs Victor and shakes loose every morsel of odious peculiarity he can grasp. Observing Victor’s pained exchanges with his dying mother, his trial of impotence, and his mastery of restaurant choking scenarios (a pass at infantilism through the compassion of strangers), Rockwell is on fire here, delivering a career-best performance in a complicated, loutish role.

Rockwell’s dynamic character shadings go a long way to patching the holes in the story. As much as Gregg evokes the strained Vulcan pinch of life on Victor’s neck, he’s not always able to convey a sense of time passage. A few of the subplots, most concerning Denny and his abstinence, are left vague outlines in the final film. The same sensation follows Victor and his own clarity, which is intended to peak with a comedic anal explosion (call it a fecal miracle), but falls short since Gregg doesn’t keep the subplot in the air long enough to digest it.

“Choke” is grim yet often wickedly funny and takes the viewer down sobering roads of sexual compulsion and familial aggravation. It’s a hypnotizing picture with a delightfully gritty awareness about it. Just ignore the abyssal dramatic potholes, and “Choke” will offer plenty of dysfunction to chew on.

B+

Leave a comment